State of Play

Exhibited Works

About

There is something ambiguous, even contradictory, about the title of Dannielle Hodson’s exhibition of new paintings ‘State of Play’. On one level, this is a phrase that suggests a clear-eyed assessment of where we’ve come from, where we are, and where we might be going, made at a remove from the frenetic business of daily life. On another, it describes the sense of flow we experience when we immerse ourselves in some seemingly inessential yet nevertheless deeply compelling activity, like children caught up in a favourite game.

The painter Philip Guston famously observed that art is a form of ‘serious play’, which requires the artist to ‘learn how to play in new ways all the time’, and this might also serve as a description of how Hodson’s canvases come into the world. Each work begins with a process of unplanned, near-automatic mark making, in which abstract passages of pigment are amassed on the support, like channeled and hyper-concentrated energies, until they reach saturation point, and legible motifs begin to suggest themselves. The characteristic result – which we see in her paintings Tree House, Estate and Noble Ruin (all works 2023) – is a teeming, carnivalesque riot of faces and bodies, ambiguous objects and dreamlike landscapes or interior spaces, which all the time threaten to slip back into pure paint, as though the only thing that was giving them definite shape was our momentary visual attention, and the contours of our individual psyches. Although these are, in a sense, narrative works, they are so dense with pictorial incident, and so little concerned with the conventional interplay of centre and periphery, composition and detail, colour and form, that the stories they suggest possess an almost fractal quality. These are images in which everything seems to happen everywhere, and all at once.

Now and then, genetic traces of great paintings from the past appear in Hodson’s canvases. Sock puppets recalls Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas (1656) in its colour palette, rough composition and cast of doll-faced, stiff-skirted aristocratic characters. The British artist adds a new, macabre note by replacing the friendly figure who we see half-silhouetted in the background of Velázquez’s work with a much more threatening presence: a 17th-century plague doctor wearing a beaked mask. If this motif triggers thoughts of the recent global pandemic, then the figures in the foreground – who form an impenetrable wall of bodies, united in their haughty intransigence – perhaps speak to another contemporary malaise, the closing of minds and hearts to differences of opinion in the social media age. (A ‘sock puppet’, we should note, is online parlance for a fake account used to amplify a particular viewpoint, and to denigrate those who do not hold it). Looking at Critical Mass, a painting Hodson has described as a ‘post-landscape, what happens when nature runs out’, we get a glimpse of a possible planetary future, in which the sun resembles a garish, synthetic wig, the sky blazes a toxic orange, and the Earth’s organic palette has been replaced by a rainbow of lurid, petrochemical tones.

What will remain in such an eventuality? Perhaps only the broken objects and mutated bodies we encounter in The Playroom and The Yard. Contemplating these works, we might be reminded of a line from T.S. Eliot’s great poem of civilizational collapse, The Waste Land (1922): ‘These fragments I have shored up against my ruin’.

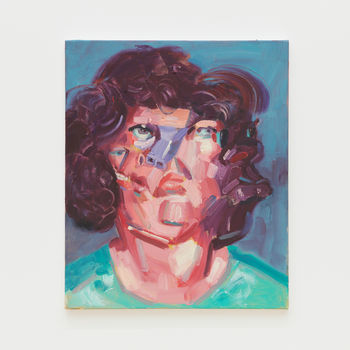

While ‘State of Play’ is an exhibition concerned, in part, with taking stock of the multiple crises facing our world, Hodson’s portrait works have a more intimate focus. These are not images of flesh-and-blood sitters, but of fictional women who have sprung from the meeting of the artist’s imagination and the demands of her paint. The colour palette of Iris is derived from Pablo Picasso’s 1930s paintings of his young daughter Maya, which depict her cuddling a baby doll – a form of ‘serious play’ in which a child adopts the persona of a parent, and anticipates the adult it will one day become. At first glance, Hodson’s portrait appears to show a grown woman in her twenties, but look closely – not only at her blue skin, but at the green swell of her hair, and even the patterns on her red sweater – and we see that she has not one face, but many, as though every stage of her personal history, from infancy to old age, exists within her simultaneously, either as a memory or as a potentiality. Perhaps some of these visages do not belong to her at all, but rather to other women – mothers, sisters, friends, enemies – who she’s absorbed into her being. Either way, she is not a fixed entity, but one that’s in constant flow. Like Hodson’s endlessly playful paintings, she contains multiple and often irreconcilable contradictions. This is what animates her, what gives her life.

Text by Tom Morton

Details

Ojiri Gallery

29 Charlotte Road, London EC2A 3PB, United Kingdom

16 Sept 2023

—

14 Oct 2023

Installation Views